THE REFLECTION OF PERCEIVING

CA319W

#301381419

YUNZE XIE

THE REFLECTION OF PERCEIVING

In modern society, all adult bodies perform actions that are so natural and justified. They do not need to think or hesitate too much when making these because they have done it thousands of times. This behavior has become part of their lives. It does not take us any time or effort to perceive what is surrounding us because as long as there are lights, all of the scenes will be projected toward our eyes. However, when we slow down the pace of life, those daily actions have room to be injected into our thinking. All of us have had the experience of being mesmerized by the view in front of us and realizing that placing our palms in front of our eyes blocks the building behind us, and these are our reflections on the act of observation. Painting, the art form, is the materialization of our thinking about the visual.

The exhibition Albers and Morandi: Never Finished has demonstrated collections of two famous artist works, which are Josef Albers's Homage to the Square series, a collection of combinations of squares with various colors and Giorgio Morandi's Naruta Mota, a series of tabletop still lines depictions that illustrate vases and vessels. These two great artists' work shows us how they thought about the action of "looking" and bring their understanding to their paintings. "Morandi's statement that nothing is more abstract than reality overshadows … almost scientific research and observation of color and light relationships.… Just like Morandi, Albers came to his identity indirectly. In these long series of parallel squares… Albers looked into what he referred to as 'interaction of color.'"(— Peter Weiermair, “Josef Albers’s Exhibition at the Museo Morandi,” in Josef Albers, Museo Morandi, Bologna, 2005) These artists have faith in abstractive art style. They all transformed what they saw into something else, rather than portraying it directly and explicitly. This type of painting requires a high level of visual understanding from the artist. It is a way of creation that all modern artists should learn from.

They play with the colors that we can observe in our daily life. Both take the use of color to a new level, while they both have different uses. The exhibition was held in David Zwirner Gallery which is located at 537 West 20th Street, New York, from January 7th to March 27th, 2021. It was organized by David Zwirner and curated by gallery Partner David Leiber. The David Zwirner gallery website offers high solution images. There are explanations about the background of both artists and a general view of how these works are exhibited. Works with similar tone art arranged next to each other. These settings contribute to a better experience for audiences while they are navigating the exhibition through the website.

Morandi's Naruta Mota series focuses on the combination of colors between bottles and jars and tablecloths. They are oil paintings that were created around the 1950s. His paintings are rarely more than one or two square feet in size, pulling the viewer in close, and their key to insight, as with dream analysis, is not their manifest content but their form of expression: the feel of his line, the touch of his brushwork, or the exact tint of his muted color (David Miller 463). These paintings depict jars or bottles of different sizes and colors placed on the same level (table) differently. These containers all have different characteristics, some with slender necks, some short and solid. It is not difficult to find that the traditional three-dimensional sense of oil painting is diluted in Morandi's works. Then he makes a new addition in the layers of light and shade and color. He added his own insights and colors to this work.

For instance, In the Natura morta con bottiglia bianca e piccola bottiglia blu, there are two separate containers of different sizes. On the left is the gray-blue, smaller-sized bottle, which has a round ball-shaped cap as an accent. On the right side is a larger white vase-like container. It has a slender neck, and the bottom of the bottle has a streamlined shape—two different shades of gray construct the background color. The dividing line between these two shades of gray suggests that the upper part is the color of the wall, while the lower part is the color of the tablecloth.

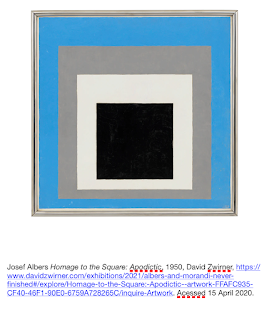

Albers' Homage to the Square series is all combinations of squares with different colors. We can only find elements of geometry in his paintings. There are no organic features. The horizontal and vertical lines are combined to build a layered frame on a two-dimensional plane. The horizontal and vertical lines are combined to build a layered frame on a two-dimensional plane. When we look at some of Albers' paintings, the Variants, as well as the Homages, we get the false sense that we are looking at overlapping color. In fact, each color is painted directly on the white ground, maintaining maximum luminosity. The illusion of transparency is a strong affirmation of the ability Albers had for finding the middle value. The placement of the color is fundamental (Garland 65). This series is also dedicated to showing the ultimate, pure colors. This explains why these squares are all filled with highly saturated colors. The purpose of this is to provoke people to think about color. How do these pure colors affect each other, and how do they affect people's visual experience?

For example, Homage to the Square: Apodictic is one of the series; in this painting, the square in the middle is pure black, while the square wrapped around it is beige, the one surrounding it is gray, and the largest square, which is also the background color, is blue. After looking at all the pieces, it is easy to see that none of the squares have the same color. They are all more or less different, and these color differences are so ambiguous. Your intuition makes you feel the difference, but when you look closely and try to point out the difference, it becomes a problem.

It is easy to see that both works question the way we look at objects. Morandi has chosen to change the picture's entire palette, making all the elements in the painting become one and more harmonious, erasing the clash of colors between the different objects, as is his usual technique. At the same time, Josef Albers is putting before us the infinite possibilities that color has. It is a question that he is always thinking about. He shows us these colorful colors through geometric figures in a simple way that could not be simpler. These colors echo each other and provoke the audience to be intensely interested in and thinking about colors.

Giorgio Morandi's purpose of drawing still life is to keep doing self-reflection on the spatial relationship between different objects and the painting's dimension. In the Natura morta con bottiglia bianca e piccola bottiglia blu, Morandi lowered the saturation of different objects. As the result, the whole picture creates a deep, harmonious atmosphere, so that those who enjoy it can't help but relax. The closeness of these different jars and the softness of the paints cancel the deepness between each subject. It is worth mentioning that sometimes, to erase the jars' depth and delicacy, he would paint or plaster them to see them from a unique perspective and record them in his paintings.

Compared to Morandi, Josef Albers put more effort into contrasting colors and questions about our intuition. He tests our senses over and over again by constructing a myriad of overlapping blocks of color. His work makes us realize that color is subjective. Albers took everything we can observe out of their three-dimensional world and keep simplifying it until only the most primitive colors remain. He demonstrated exactly what he wanted to teach his students. Albers' goal as a teacher was to teach his students how to see, to develop color-sensitive eyes through their experimentation with color. He was a phenomenologist and did not present a theory or a system to his students, instead asking them to find backgrounds that make 2 colors look alike (Harris 520).

Similarly, here Albers tries to use these simple and clear blocks of color to awaken the viewer to the act of "looking". This is something that is even more important for people living in modern society. Although technology has made it possible for everyone to see a rich variety of stunning views, most people still do not have an aesthetic. Homage to the Square series have the power to recall independent thinking on cognition.

What makes these two great artists timeless is that they are challenging the vision, challenging the phenomena that everyone has taken for granted, and making the ordinary extraordinary. They cut apart this commonplace act, revisit it, recombine it, and then give their own answer. Both of them keep thinking about our instincts in the process of creation. Moreover, the audience can also resonate with both artists when they view their works. Because in the process of viewing, the viewer is allowed to step out of his or her usual world of vision and participate in the artists' reflections.

Morandi's answer is to create a dreamy and relaxed atmosphere, inviting each viewer to enter his world and to understand the still life in front of him from his perspective. It can be said that Morandi's works are more emotional, he hides the answers to his visual thoughts in these jars and jars, waiting for the viewers to uncover them slowly. On the other hand, Albers is rational, and like a science teacher, he arranges the possibilities of color in a geometric form. He put his answers on the paintings and showed the audience the beauty of color.

Notes for bibliography:

Garland, Patricia Sherwin. “Josef Albers: His Paintings, Their Materials, Technique, and Treatment.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol. 22, no. 2, 1983, pp. 62–67. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3179502. Accessed 15 Apr. 2021.

Harris, James C. “Homage to the Square.” Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 5, 2007, p. 520.

MILLER, J. DAVID. “Unraveling the Enigma of Giorgio Morandi: A Psychoanalytic Strategy.” American Imago, vol. 72, no. 4, 2015, pp. 451–476. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26305131. Accessed 22 Mar. 2021.

Stephanie D'Alessandro. “Still Life.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 29, no. 2, 2003, pp. 80–95. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4121068. Accessed 19 Mar. 2021.

Link for the exhibition:

https://www.davidzwirner.com/exhibitions/2021/albers-and-morandi-never-finished

Comments

Post a Comment